Go beyond your boundaries and explore the world as never before.

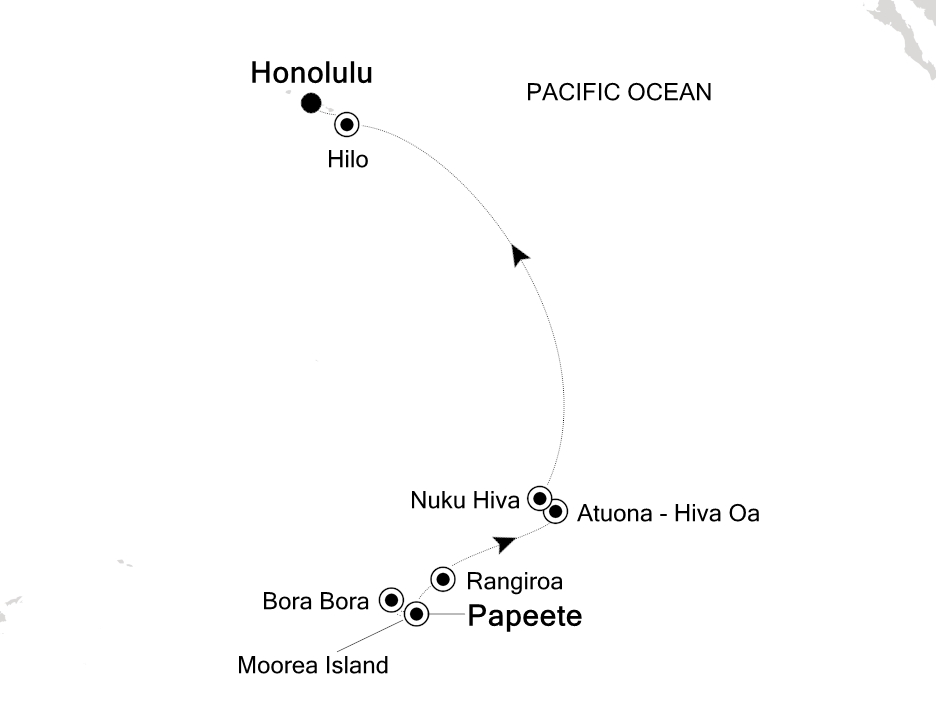

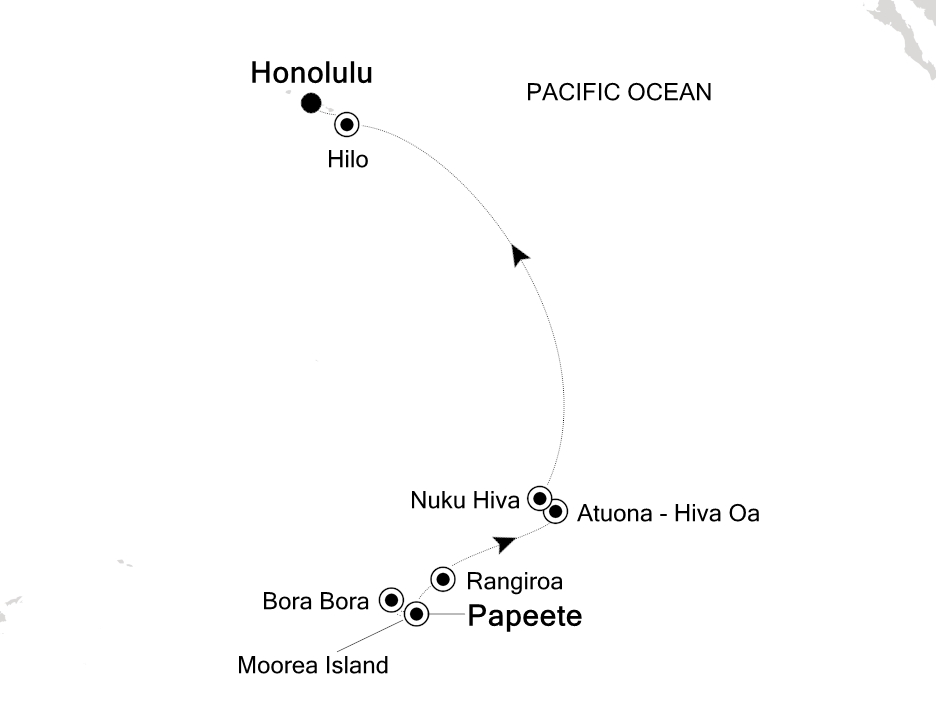

Moorea is called the "sister island" of Tahiti and its proximity—just 19 km (12 mi) away across the Sea of Moon—has assured a steady stream of both international and local visitors. Many Tahitians have holiday homes on Moorea and hop over in their boats or take the 30-minute ferry. The draw is South Seas island charm and a relatively slow-paced life. Moorea is an eighth of the size of Tahiti but packs all the classic island features into its triangular shape. Cutting into the northern side of the island are the dramatic Opunohu Bay and Cook's Bay, the latter backed by the shark-toothed Mt. Mouaroa and home to many resorts and restaurants. Between the two bays majestic Mt. Rotui rises 2,020 feet (616 meters) and steep, jagged mountain ridges run across the island. From the Belvedere lookout there are awesome views of these bays and mountains, including the tallest peak—the thumb-shaped Mt. Tohiea reaching 3,960 feet (1,207 meters) into the clouds. Moorea is ringed by a coral reef enclosing a beautiful and quite narrow lagoon. Unlike other islands in the Society group, Moorea has only a couple of motu (islets) and they are located off the northwest corner. The island's rugged peaks and deep bays are said to be the inspiration for James A. Michener's mythical isle of Bali Hai, although historians dispute this claim. It's also believed to be the "birthplace" of the legendary overwater bungalow: a trio of Californian guys who came to Moorea in the 1950s and became known as the Bali Hai boys reportedly dreamt up this unique style of hotel room. Today there are seven resorts and about 24 smaller hotels and pensions, acres of pineapple plantations, and one of only two golf courses in French Polynesia. Moorea is an easy island to explore by car. The one coastal road is just 61 km (37 mi) long, and the best part of a day is needed to travel the road and stop off at the villages, bays, little churches, and cafés along the way and to travel into the interior to the Belvedere lookout and the marae (ancient temples). The lagoon and bays can be discovered on organized excursions that may include a picnic lunch on one of the motu at the island's northwest corner. There are also small motorboats for hire for a half or full day, with no license required. You won't find too many tracks of endless white sands on Moorea; however, the top resorts have lovely man-made beaches and the lagoon-side pensions and lodges always have at least a little patch of sand.

Rangiroa, or "Endless Sky" in Tahitian, is French Polynesia's largest atoll. A long, narrow grouping of 415 small motu strung together in a misshapen circle, it harbors a lagoon so large the entire island of Tahiti could fit in it. It's also impossible to see from one side of the lagoon to the other. Rangiroa's tourism industry has been built around the lagoon and the two passes (Avatoru and Tiputa) that connect it to the ocean. Divers descend on Rangi, as it's nicknamed, to "shoot the pass." The atoll's main town, Avatoru, and the village of Tiputa lie in the northern section of the atoll.

Author Herman Melville summed up Nuku Hiva as a "country that no description could fit the beauty." Melville deserted his ship, the whaler Acushnet in the Marquesas and for a short time lived among the Typee people. At 329 square km (127 square mi), this is the largest of the Marquesas Islands; it was also the inspiration for two of Melville's novels, Typee and its sequel Omoo.With towering mountains, eight magnificent harbors, and one of the world's highest waterfalls, Nuku Hiva is richly blessed. Few doubt that its 2,400 inhabitants live in paradise.

In comparison to Kailua-Kona, Hilo is often described as "the old Hawaii." With significantly fewer visitors than residents, more historic buildings, and a much stronger identity as a long-established community, this quaint, traditional town does seem more authentic. It stretches from the banks of the Wailuku River to Hilo Bay, where a few hotels line stately Banyan Drive. The characteristic old buildings that make up Hilo's downtown have been spruced up as part of a revitalization effort.

Nearby, the 30-acre Liliuokalani Gardens, a formal Japanese garden with arched bridges and waterways, was created in the early 1900s to honor the area's Japanese sugar-plantation laborers. It also became a safety zone after a devastating tsunami swept away businesses and homes on May 22, 1960, killing 60 people.

With a population of almost 50,000 in the entire district, Hilo is the fourth-largest city in the state and home to the University of Hawaii at Hilo. Although it is the center of government and commerce for the island, Hilo is clearly a residential town. Mansions with yards of lush tropical foliage share streets with older, single-walled plantation-era houses with rusty corrugated roofs. It's a friendly community, populated primarily by descendants of the contract laborers—Japanese, Chinese, Filipino, Puerto Rican, and Portuguese—brought in to work the sugarcane fields during the 1800s.

One of the main reasons visitors have tended to steer clear of the east side of the island is its weather. With an average rainfall of 130 inches per year, it's easy to see why Hilo's yards are so green and its buildings so weatherworn. Outside of town, the Hilo District has rain forests and waterfalls, a terrain unlike the hot and dry white-sand beaches of the Kohala Coast. But when the sun does shine—usually part of nearly every day—the town sparkles, and, during winter, the snow glistens on Mauna Kea, 25 miles in the distance. Best of all is when the mists fall and the sun shines at the same time, leaving behind the colorful arches that earn Hilo its nickname: the City of Rainbows.

The Merrie Monarch Hula Festival takes place in Hilo every year during the second week of April, and dancers and admirers flock to the city from all over the world. If you're planning a stay in Hilo during this time, be sure to book your room well in advance.

Here is Hawaii's only true metropolis, its seat of government, center of commerce and shipping, entertainment and recreation mecca, a historic site, and an evolving urban area—conflicting roles that engender endless debate and controversy. For the visitor, Honolulu is an everyman's delight: hipsters and scholars, sightseers and foodies, nature lovers and culture vultures all can find their bliss.

Once there was the broad bay of Mamala and the narrow inlet of Kou, fronting a dusty plain occupied by a few thatched houses and the great Pakaka heiau (shrine). Nosing into the narrow passage in the early 1790s, British sea captain William Brown named the port Fair Haven. Later, Hawaiians would call it Honolulu, or "sheltered bay." As shipping traffic increased, the settlement grew into a Western-style town of streets and buildings, tightly clustered around the single freshwater source, Nuuanu Stream. Not until piped water became available in the early 1900s did Honolulu spread across the greening plain. Long before that, however, Honolulu gained importance when King Kamehameha I reluctantly abandoned his home on the Big Island to build a chiefly compound near the harbor in 1804 to better protect Hawaiian interests from the Western incursion.

Two hundred years later, the entire island is, in a sense, Honolulu—the City and County of Honolulu. The city has no official boundaries, extending across the flatlands from Pearl Harbor to Waikiki and high into the hills behind.

The main areas (Waikiki, Pearl Harbor, Downtown, Chinatown) have the lion's share of the sights, but greater Honolulu also has a lot to offer. One reason to venture farther afield is the chance to glimpse Honolulu's residential neighborhoods. Species of classic Hawaii homes include the tiny green-and-white plantation-era house with its corrugated tin roof, two windows flanking a central door and small porch; the breezy bungalow with its swooping Thai-style roofline and two wings flanking screened French doors through which breezes blow into the living room. Note the tangled "Grandma-style" gardens and many ohana houses—small homes in the backyard of a larger home or built as apartments perched over the garage, allowing extended families to live together. Carports, which rarely house cars, are the island's version of rec rooms, where parties are held and neighbors sit to "talk story." Sometimes you see gallon jars on the flat roofs of garages or carports: these are pickled lemons fermenting in the sun. Also in the neighborhoods, you find the folksy restaurants and takeout spots favored by the islanders.

Here is Hawaii's only true metropolis, its seat of government, center of commerce and shipping, entertainment and recreation mecca, a historic site, and an evolving urban area—conflicting roles that engender endless debate and controversy. For the visitor, Honolulu is an everyman's delight: hipsters and scholars, sightseers and foodies, nature lovers and culture vultures all can find their bliss.

Once there was the broad bay of Mamala and the narrow inlet of Kou, fronting a dusty plain occupied by a few thatched houses and the great Pakaka heiau (shrine). Nosing into the narrow passage in the early 1790s, British sea captain William Brown named the port Fair Haven. Later, Hawaiians would call it Honolulu, or "sheltered bay." As shipping traffic increased, the settlement grew into a Western-style town of streets and buildings, tightly clustered around the single freshwater source, Nuuanu Stream. Not until piped water became available in the early 1900s did Honolulu spread across the greening plain. Long before that, however, Honolulu gained importance when King Kamehameha I reluctantly abandoned his home on the Big Island to build a chiefly compound near the harbor in 1804 to better protect Hawaiian interests from the Western incursion.

Two hundred years later, the entire island is, in a sense, Honolulu—the City and County of Honolulu. The city has no official boundaries, extending across the flatlands from Pearl Harbor to Waikiki and high into the hills behind.

The main areas (Waikiki, Pearl Harbor, Downtown, Chinatown) have the lion's share of the sights, but greater Honolulu also has a lot to offer. One reason to venture farther afield is the chance to glimpse Honolulu's residential neighborhoods. Species of classic Hawaii homes include the tiny green-and-white plantation-era house with its corrugated tin roof, two windows flanking a central door and small porch; the breezy bungalow with its swooping Thai-style roofline and two wings flanking screened French doors through which breezes blow into the living room. Note the tangled "Grandma-style" gardens and many ohana houses—small homes in the backyard of a larger home or built as apartments perched over the garage, allowing extended families to live together. Carports, which rarely house cars, are the island's version of rec rooms, where parties are held and neighbors sit to "talk story." Sometimes you see gallon jars on the flat roofs of garages or carports: these are pickled lemons fermenting in the sun. Also in the neighborhoods, you find the folksy restaurants and takeout spots favored by the islanders.

World Cruise Finder's suites are some of the most spacious in luxury cruising.

Request a Quote - guests who book early are rewarded with the best fares and ability to select their desired suite.